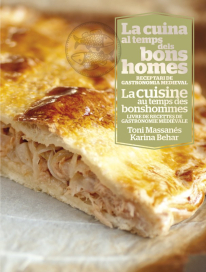

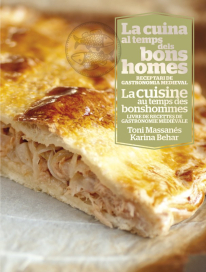

History of Cuisine in the Time of the Cathars: Medieval Gastronomy

What did the Cathars eat?

In the Middle Ages, food differentiated the communities that lived together, marking whether they coexisted better or worse in our territory. The Arabs who still populated New Catalonia, the Jews who were spread out in the streets of the most important cities and towns and, obviously, the Christians. They all displayed the different traditions, rites and food prohibitions that identified them as a group. It should not surprise us, then, that when a renewing current emerged from within Christianity that claimed original purity, it immediately generated a doctrine of food as a reaction to the excesses of the official church.

In fact, the Cathar food ideology merely collected the prescriptions of the moralists of the time and carried them to their ultimate consequences. Thus, if meat—both figuratively and literally—was considered sin, eating it had to be prohibited not only during established periods of abstinence but always. Everything that was a product of generation, that is, of sex, was considered impure. Therefore, not only was the consumption of meat to be rejected, but also that of eggs, milk, and their derivatives. On the other hand, primitive medieval biology understood that fish was a spontaneous fruit of the water, not from fornication, therefore its consumption was pure.

Those who, driven by the ideal of purity, dedicated themselves to proclaiming the Cathar faith, becoming spiritual guides of this emerging parallel church, wanted to be an example of virtue that the people could look up to. These types of Cathar priests were known as Good Men or Perfects due to their high level of self-discipline. They only ate vegetables and fish, and even three days a week they went on bread and water.

But this was only the practice of the Perfects.

The majority of Cathar followers ate anything and only followed the prescriptions of the Perfects when they met with them for certain meals. The faithful who travelled along Camí dels Bons Homes, leading flocks or fleeing the Inquisition, were normal people, lovers of the pleasures of life, eating meat and cheese. For breakfast they liked fried eggs with bacon. In the inns and taverns along the way, they shared experiences and heresy with other travellers around a jug of wine. And they would savour simple but delicious dishes from their wonderful cuisine.

And how do we know all this?

Well, because, among other research, we have focused on analysing the Inquisition records against the last Cathars and found references to dishes, preparations and products, which we compared with the recipe books of the time in order to extract—once interpreted—these recipes. Let's not forget that some of the first European cookbooks written in Romance languages were written in Catalan, such as the so-called Sent Soví.

It is true that the medieval cookbooks we have preserved are from aristocratic kitchens, and our faithful Cathars were humble, common people. Also, at that time, food was very different depending on the social class to which one belonged, as Doctor Antoni Riera Melis, who is the foremost specialist we have in this field, explains. But it is no less true that the different strata—nobles, monks and peasants—of that food system obviously shared many culinary principles.

As the philosopher and mathematician, Rudolf Grewe pointed out when he produced the critical edition of the Sent Soví manuscripts, it is clear that Catalan cuisine of the time had significant influence.

Surely, its main appeal was knowing how to gather, upon the common foundation of classical and Visigothic heritage, the refined influences of Andalusian culture, which was the guardian of Mediterranean wisdom and the transmitter of Eastern treasures.

Apart from many products that the Arabs introduced or reintroduced to the Peninsula (among which some are still part of our food idiosyncrasy such as rice, spinach, aubergines, lemons, sugar, noodles, etc.), an incipient taste for vegetables (quite disdained until then by the barbarian carnivores of the north but which, as you can see, over time has ended up prevailing) and the presence of certain fish and other products typical of the Mediterranean environment characterised this cuisine.

Also, a good number of exquisite sauces (such as ginestrada, a cream made with rice, saffron, and almond milk), the custom—widely exported, by the way—of cooking poultry with citrus (does canard à l’orange ring a bell?) and some delicately perfumed dishes with a thousand spices (because ginger arrived long before sushi, folks!), even rose water.

This stylistic differentiation in the art of preparing food in medieval Catalonia was, in fact, quite shared with Occitania. Cuisine is an excellent example of cultural dynamics and, just as we shared beliefs and songs, in the Middle Ages we also shared tastes and ways of eating with our almost sibling neighbours, the Provençals. Few traces remain of their culinary production. Among these, a manuscript in Latin that is preserved in the National Library of Paris entitled Modus viaticorum preparandorum et salsarum corroborates the unity of style of medieval Catalan and Occitan culinary praxis.

Because Catalano-Occitan cuisine was, in the Middle Ages, an expression of that civilisation which took shape on both sides of the Pyrenees. A culture that the Catalan and Occitan lords, the troubadours and the Cathars tried to defend against the crusade of France and Rome. A culture that had created landmarks of such beauty as courtly love. A cuisine that has evolved over time, incorporating countless new ingredients and methods without losing its original personality, eventually becoming what we now know as Catalan cuisine today.

A cuisine of which you can taste some examples here and now.

Toni Massanes

Director of Fundació Alícia and researcher at the Food Observatory of the Barcelona Science Park